Household Energy Efficiency Ratings ‘Inaccurate and Misleading’

Consumer Group Which? Calls for Overhaul of Entire EPC System

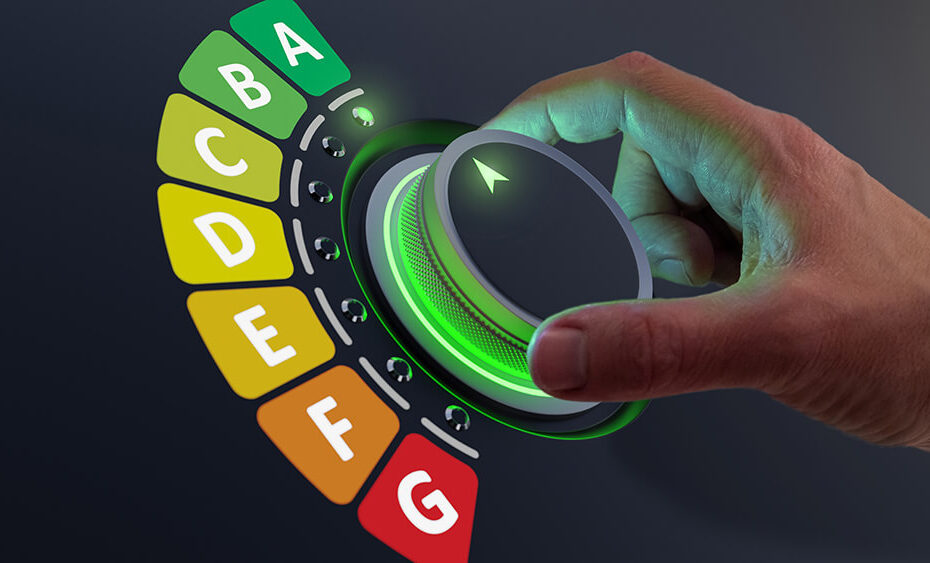

A report has claimed that the green energy ratings for homes are “inaccurate” and “misleading”. Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs), which rate properties from A to G based on their energy efficiency, are unreliable and confuse homeowners, landlords, and tenants, according to the consumer group Which?.

Which? has called for a radical overhaul of the EPC system, which has led to some homeowners spending thousands of pounds on energy-efficient upgrades. Obtaining an EPC certificate is a legal requirement before selling or renting out a property. Landlords face a penalty of up to £5,000 for not meeting the minimum rating of E. EPC assessments typically cost between £35 and £100.

The Which? report stated: “There is now considerable evidence that too many EPCs do not provide an accurate assessment of the energy efficiency of a home. The metrics that are used are confusing for consumers, and there is a need to provide new information that would support consumers in the decisions they need to make.”

The report cites a Leeds Beckett University study that found at least 27 per cent of all EPCs completed between 2008 and 2016 have a discrepancy that suggests an error was made. Another study by University College London found that for properties where at least two EPCs exist, up to 62 per cent of EPCs may be incorrect.

Only 36 per cent of the UK population understand what their EPC rating is, according to a recent Government survey. And only 29 per cent of those that were aware of their EPC said they had seen the section with advice on how to improve their rating.

The Which? report added: “The metrics and information in many EPCs may be misleading, and homeowners, tenants, landlords, and policymakers could be making decisions based on inaccurate information”.

This comes after Michael Gove, the Housing Secretary, said last year that the EPC system – introduced by Labour in 2007, in compliance with a European Union directive – suffered from “a number of weaknesses”. He added that EPCs drove “perverse outcomes”, amid fears property owners would be left unable to sell or rent.

In September, Rishi Sunak scrapped plans to require rental properties to be more energy-efficient. The Government had intended to change the law so that rental properties would require a minimum energy efficiency rating of C by 2025 when leased under new tenancies. To meet the rules, property-owners would have had to spend an average of £8,000 on insulation and other improvements, according to research by the estate agents Hamptons. Many landlords had already spent thousands of pounds to raise their rating in preparation for the 2025 deadline when the requirement was scrapped.

In December, the Government launched a consultation on the Home Energy Model (HEM), a new methodology to rate the energy performance of homes. The model is set to replace the Standard Assessment Procedure which underpins the EPC system after the HEM is implemented in 2025. Landlords are concerned that the change may require them to reverse costly eco-friendly upgrades.

Daniel Särefjord, the Chief Executive of Aira UK, a clean energy technology firm, said: “The Energy Performance Certificate regime is outdated, counterintuitive, and badly designed to meet consumer demand for accurate home energy efficiency ratings. EPCs should have a greater focus on the impact of the home on the climate, a metric that is lacking at this time.”

Chris Norris, of the National Residential Landlords Association, said EPCs were a “blunt tool”. “They [EPCs] are not fit for purpose. There’s a lot of inaccuracy because they are based on lots of assumptions about building, such as the extent of wall insulation. They’re a blunt tool and not very useful if you’re a landlord wanting to make an investment or a tenant wanting to know how energy-efficient a property is. If properties are given a very low rating, it’s hard to get a mortgage – lenders don’t want to touch it, and that applies to buy-to-let and residential.”

He added that there is a “lack of clarity” in the system because there are two EPC measures currently used – a property’s carbon impact and the cost to heat it. “In the landlord community, there is lots of unease – we don’t know which measure we should be favouring. We’re caught between a rock and a hard place.”

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities was approached for comment.

The Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) system, introduced in 2007 to comply with a European Union directive, has come under scrutiny for its inaccuracy and misleading information. The system rates properties from A to G based on their energy efficiency, but multiple studies have found significant discrepancies and errors in the ratings.

A report by the consumer group Which? highlights the shortcomings of the EPC system, citing evidence that a considerable number of EPCs do not accurately assess a home’s energy efficiency. The report notes that the metrics used in EPCs are confusing for consumers and that there is a need for new information to support consumers in making informed decisions about energy efficiency.

One study cited in the report, conducted by Leeds Beckett University, found that at least 27 per cent of all EPCs completed between 2008 and 2016 had a discrepancy suggesting an error was made. Another study by University College London revealed that for properties with at least two EPCs, up to 62 per cent of EPCs may be incorrect.

These inaccuracies have led to confusion and potential misinformation for homeowners, landlords, and tenants. Only 36 per cent of the UK population understand their EPC rating, according to a recent Government survey, and only 29 per cent of those aware of their EPC had seen the section with advice on how to improve their rating.

The Which? report emphasises that the metrics and information in many EPCs may be misleading, leading to decisions being made based on inaccurate information by various stakeholders, including homeowners, tenants, landlords, and policymakers.

The issue of inaccurate EPCs has not gone unnoticed by the Government. Michael Gove, the Housing Secretary, acknowledged last year that the EPC system suffered from “a number of weaknesses” and drove “perverse outcomes”, citing fears that property owners might be unable to sell or rent due to the ratings.

In September 2022, Rishi Sunak, the then Prime Minister, scrapped plans to require rental properties to meet a minimum energy efficiency rating of C by 2025 for new tenancies. This decision came after many landlords had already invested thousands of pounds to raise their properties’ ratings in preparation for the 2025 deadline, only to have the requirement scrapped.

In an effort to address the issues with the EPC system, the Government launched a consultation in December 2022 on the Home Energy Model (HEM), a new methodology for rating the energy performance of homes. The HEM is set to replace the Standard Assessment Procedure, which underpins the current EPC system, after its implementation in 2025. However, landlords are concerned that the change may require them to reverse costly eco-friendly upgrades they had previously undertaken.

Daniel Särefjord, the Chief Executive of Aira UK, a clean energy technology firm, criticised the current EPC regime, describing it as “outdated, counterintuitive, and badly designed to meet consumer demand for accurate home energy efficiency ratings.” He emphasised the need for EPCs to have a greater focus on the impact of homes on the climate, a metric currently lacking in the system.

Chris Norris, of the National Residential Landlords Association, echoed these sentiments, labelling EPCs as a “blunt tool” that is “not fit for purpose.” He highlighted the inaccuracies stemming from assumptions made about building characteristics, such as the extent of wall insulation, and questioned the usefulness of EPCs for landlords looking to make investments or tenants seeking to understand a property’s energy efficiency.

Norris also pointed out the lack of clarity in the system due to the use of two different EPC measures: a property’s carbon impact and the cost to heat it. This has created unease within the landlord community, as they are unsure which measure they should prioritise, leaving them “caught between a rock and a hard place.”

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities was approached for comment on the issues raised in the report, but no response was provided.

As the UK continues to grapple with the challenges of improving energy efficiency and reducing carbon emissions in the housing sector, the findings of the Which? report underscore the need for a comprehensive overhaul of the EPC system. Accurate and reliable energy efficiency ratings are crucial for informing consumers, landlords, and policymakers, and for driving meaningful progress towards a more sustainable housing stock.